2018 is an election year in Azerbaijan. The authorities may have the streets on lockdown, but the fight against dissent in cyberspace is just beginning.

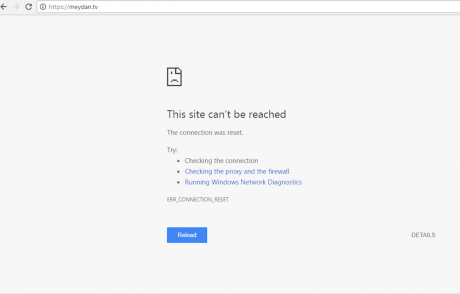

Last week, somebody broke into MeydanTV’s Facebook. By Monday, the Berlin-based online news platform finally restored its access to the page — but had lost years of posts and nearly 100,000 subscribers (the publication had experienced a series of DDoS attacks on its site earlier in January). Anybody who knows the parlous state of freedom of speech in Azerbaijan knows of MeydanTV. The site’s independent journalism has won it no friends in the South Caucasus state, where its journalists are routinely harassed.

In recent weeks, reports have abounded of DDoS attacks and hacking of Facebook and email accounts of Azerbaijani dissidents and their supporters. Both of us can attest from personal experience that the attackers have upped their game — using surveillance technologies such as Deep Packet Inspection (DIP) and spearphishing attempts. As we enter 2018 and a presidential (re)election in October, these moves attest to a digital crackdown in Azerbaijan – policing the internet and deterring online activism.

The block doctrine

One development at the end of last year showed a new stage of regime mobilisation against online dissent. A legal amendment last year allowed Azerbaijan’s state institutions to block websites on the grounds of national security — and MeydanTV’s was among them.

Furious, five blocked media outlets contested the ruling. During an appeals hearing on 19 December 2017, a representative from the Ministry of Communication (the government body that carried out the blocking) said the websites were blocked not at his ministry’s orders, but by the prosecutor’s office.

Bakhtiyar Mammadov, who testified on behalf of the ministry, declared Meydan TV, Radio Azatliq (RFE/RL’s Azerbaijani service), and the independent Azadliq newspaper (unrelated to Azadliq Radio), Turan TV, and Azerbaijan Hour were to be the first on the list of websites to be blocked following the amendments. “We received a letter from the prosecutor’s office telling us to take immediate measures against these websites,” said Mammadov.

While Mammadov urged the judge to dismiss the lawyers’ appeal to unblock the websites, he argued that blocking only boosted their readership, and that dedicated users can still find ways to access them. At the end of the day, the court in Baku ruled against unblocking the online news outlets.

Hacking away at the opposition

With the right know-how, getting around a block isn’t too difficult — you can use a VPN or a mirrored website. Too bad that the authorities are eager to target those who’d want to do so.

In a recent interview, a dissident activist from Azerbaijan told us of two types of politically-motivated hacking that the regime uses today. Firstly, there’s hacking of Armenian websites (Azerbaijan technically remains at war with its western neighbour over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh), secondly, there’s the hacking of civil society activists’ email and social media accounts. In the case of civil society activists, a hacker picks his target, acquires access to just one account and once in, has access to emails and contacts of everyone else in the contact list.

It seems clear that the authorities have stepped up their internet policing measures ahead of elections in October

Hacking Facebook accounts isn’t too difficult, as most accounts are linked to a phone number and therefore a mobile network operator. In a country where these firms are under the watchful eye of the authorities, requesting a password via mobile device to reset the password is simple. With one SMS, the hacker gets hold of the account and the damage is done.

Recent examples include the hacking of Facebook profiles and pages of political figures Ali Karimli and Camil Hasanli. As former presidential candidate Hasanli put it, the damage inflicted was extensive. He lost 75,000 of his 108,350 subscribers, as well as all the posts, photos, videos, and articles he’d shared since 2013.

This wasn’t the first time Hasanli has been hacked, but he believes the hackers have now raised the stakes. “My accounts were hacked one year ago, around the time of a [opposition] political rally, but I was able to quickly regain access to my account,” he recalls. This time, says Hasanli, the hacker got back into his pages several times before finally being shut out. He believes this was more than an ordinary hacker attack, and suspects that updated technology was used.

The possibility of new technology is something for forensic specialists to establish. But to any observer, it seems clear that the authorities have stepped up their internet policing measures ahead of elections in October, and are ready to deploy all kinds of tricks to keep dissident voices muted offline and online.

Denial of service, denial of dissent

In this March 2017 report, the secure hosting service VirtualRoad analysed the types and frequency of DDoS attacks in Azerbaijan. A DDoS or Distributed Denial of Service attack is an attempt to make an online service (often a bank or news website) unavailable, by overwhelming it with traffic from multiple sources.

VirtualRoad states that all DDoS attacks observed between October 2016 and March 2017 originated from dedicated servers operated by Azerbaijani system administrators, which made VirtualRoad conclude that the attackers were close to the country’s cybersecurity community. VirtualRoad also discovered botnet attacks against the small independent news website abzas.net and azadliq.info before these websites were blocked.

The DDoS attacks Meydan TV experienced in January of this year, however, point to new revelations. MeydanTV’s website managers tracked the sources of the DDoS attacks and discovered that this time they were carried out from from India, Vietnam, Romania, Brazil, and Indonesia. And this time, defending the website was much harder.

Now that much of Azerbaijan’s civil society is out of the picture, the goal is to render the opposition totally harmless

As a result, Meydan TV’s mirror website was disabled in the first DDoS attack of this style. Not even the site’s Cloudflare service (which provides DDoS protection and firewall) were enough to keep the website secure. As the attacks continued over several days, it was difficult for the news outlet to continue the work as usual.

In addition to DDoS attacks, Azerbaijani activists have been subject to other forms of intimidation and surveillance including Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) — also known as information extraction, which in normal circumstances is used for innocuous reasons, but in the wrong hands can be used for surveillance, and snooping over personal content, spear phishing, and the creation of impersonating accounts.

In 2014, Citizen Lab revealed Azerbaijan was among the customers of Hacking Team, from which the country’s Ministry of Internal Affairs had bought Remote Control Spyware (RCS) technology. In research published last March, Amnesty International concluded that spearphishing and other forms of attacks against Azerbaijani dissidents began in November 2015, the year when Azerbaijan had its parliamentary elections — and when the regime woke up to what was happening online.

The calm before the fraud?

With presidential elections scheduled for 17 October, Azerbaijan’s political arena is going to be on lockdown. The elected president will stay in power for the next seven years based on the 29 amendments voted through via a country-wide referendum two years ago.

The new president will also have a range of powers, including dismissing parliament and calling for early presidential elections. The current head of state, president Ilham Aliyev, took power in 2003, secured a second presidential term in 2008 and in 2009 scrapped presidential term limits all together — this allowed him to run and successfully win the presidential elections in 2013. Following the 2016 referendum, Aliyev appointed his wife Mehriban Aliyeva to the position of the country’s First Vice President, a seat in the government also made possible by the 2016 referendum.

The country’s electoral history is marred by vote rigging and ballot stuffing, to name a few. Elections are held in an unequal environment where activists, dissidents and civil society representatives were and are harassed, intimidated and silenced. Aliyev has won every single presidential election with an over 80% majority since taking the seat from his father, the late Heydar Aliyev, and Yeni Azerbaijan, the ruling party, has managed to win majority in all parliamentary elections since the Aliyev family took over the presidency.

According to Camil Hasanli, the political, social and economic environment established in Azerbaijan is an unequal playing field. The opposition does not have access to television (which remains a key point of news access among wider population); civil society has been silenced; independent media is blocked and so is the opposition media; while critical voices have been either arrested or forced out of the country. “In this environment, the only place remaining for influencing public opinion is Facebook,” notes Hasanli. And so it is not surprising that the authorities are using various methods against online dissidence to take the remaining free space. Scores of Azerbaijani citizens have been questioned for posting critical commentary on Facebook, or simply liking a social media status, or clicking “attend” for political rallies. There are currently four bloggers who are serving a prison term. Even diplomats have paid a heavy price for voicing their concerns on social media.

While Azerbaijan is certainly far from Russia’s troll factories, it is catching up

A number of political figures and experts interviewed for this story commented that attacks on the internet usually take place during certain political events, elections, rallies and protests. And given this year is too an election year it is not totally surprising to see more online activity taking place and new targets selected. Now that much of Azerbaijan’s civil society is out of the picture, the goal is to render the opposition totally harmless. This includes hacking of political leaders’ Facebook pages and their accounts, as well as pressure against prominent dissident bloggers, using their families as baits.

Two prominent cases involve video bloggers Orduhan Temirhan and Mammad Mirza, both of whom live abroad. In June 2017, some 12 members of Orduhan’s family members were detained, questioned and asked to demand the Netherlands-based Temirhan stop his activism in an exchange for their freedom. While in January this year, Mirza’s father was briefly detained and then released in an exchange for his brother-in-law. The family has denounced Mirza while the blogger is refusing to stop any of his work. Mirza in an interview with Meydan TV said he has no intention of stopping and plans to attend a rally in Strasbourg in February to speak of the threats against his family.

While Mirza and Ordukhan are committed to their cause, so are Azerbaijani trolls who are committed to the jobs they have been given. Anecdotal evidence suggests some of these fierce online commentators are civil servants, pro-government journalists and members of the ruling party branch. Often their comments are copy paste or excerpts from statements made by the President and other government officials. Their ability to engage in a healthy debate online is weak say political activists often subject to their harassment. There are users with assigned user accounts, but there are also users that operate more than one account disguised under different names.

While Azerbaijan is certainly far from Russia’s troll factories, it is catching up.